The Heiligenberg

The Heiligenberg, with its two conspicuous peaks, rises above the mouth of the Neckar into the plains of the Rhine river. It belongs to the Odenwald mountain range. Apart from the north-eastern saddle to the “Zollstock”, it is almost entirely separate from the rest of the mountain range . Otherwise it has relatively steep flanks and thus has, over time, offered several advantages:

-

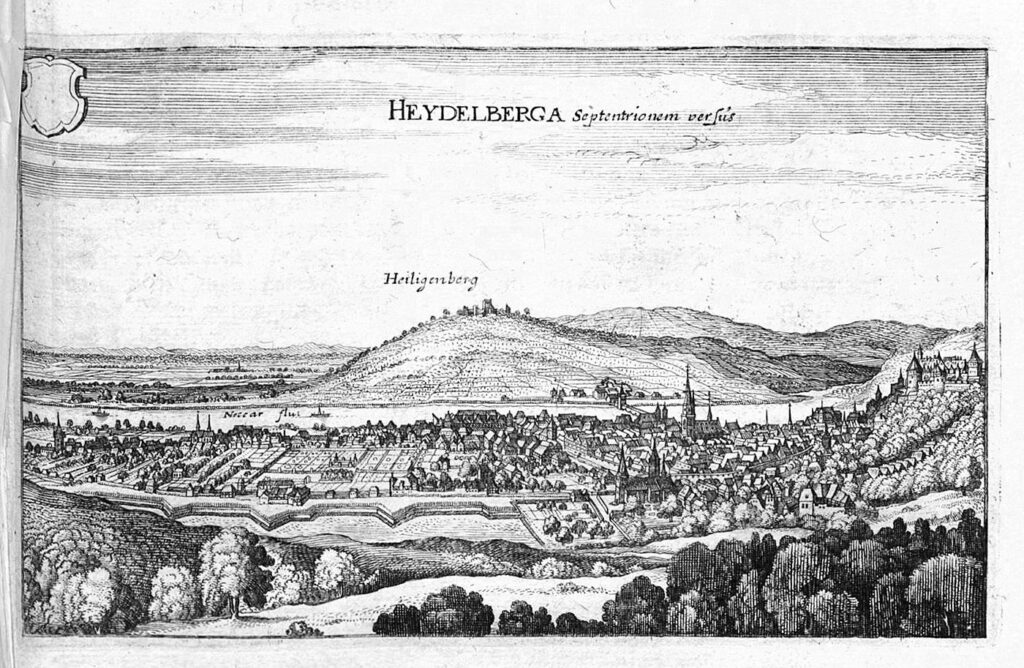

Blick auf den Heiligenberg vom Neckar aus

Important military and trade routes on land and sea could be controlled from here, in both north-south and east-west directions.

- Those who settled on the peaks, which were treeless until the 19th century, had a vast view in all directions: to the north as far as Worms, to the west as far as the Palatinate Forest, to the south-west as far as Speyer, and to the south as far as the northern Black Forest and the Neckar valley to Schlierbach. Larger buildings on the summit were also seen from afar in the plain and also served as a point of reference.

- Due to its relatively steep shape, it was easy to defend against attacks.

- Large parts of the Heiligenberg are made of Bunter sandstone (Buntsandstein), which is easy to dismantle and use as building material.

- The brown iron ore that is found in the Bunter sandstone (Buntsandstein) contributes to a measurably increased magnetism, which is perceived by sensitive people as pleasant and it has certainly contributed to the millennia-long use as a sacred place.

- The only downside is the poverty found by the springs that are located higher up, only the “Bitterbrunnen” provides water regularly at higher altitudes, or (up until a few years ago) so does the “Zollstockbrunnen” which is not far away.

Heidelberg mit Heiligenberg 1654. Merian

The mountain only got its name in the late Middle Ages, when St. Michael’s monastery was settled in the 13th century by monks from the Premonstratensian monastery of All Saints in the Black Forest. The mountain was henceforth called „mons omnium sanctorum“ or „Allerheiligenberg“, from which today’s short form is derived. In the Early and High Middle Ages it was called „Aberinesberg“ or „Aberinesburg“, which was also piously corrupted by the monks in texts to „Abrahamsberg“.

Neolithic to Urnfield Age

The oldest finds date from the Early Neolithic around 5000 BC. They are shards of vessels from band ceramics, however they do not provide conclusive evidence of a settlement. Shards of vessels from the Rössen culture, flint artifacts and arrowheads from the entire area of the later inner Celtic wall suggest a settlement in the Middle Neolithic. In contrast, there are not many finds from the Bronze Age, apart from those from the late phase of the Urnfield Culture around 1000 BC., which suggest an intensive settlement.

Funde des Neolithikums und der Bronzezeit © KMH (E. Kemmet)

Celts

A rather intensive Celtic settlement can be archaeologically proven between 700 and 200/150 BC. It begins with a Celtic fortification and a “princely seat” along with numerous domestic dwellings that probably start from the northern hilltop and possibly end with a late Celtic “oppidum” about 200 years before the turn of the era.

Visible findings in the area, some – unfortunately – few excavations and, above all, chance finds give a vague picture of the Celtic presence on the Heiligenberg.

Großer doppelkonischer Topf aus der Lantènezeit © KMH (E. Kemmet)

In 1860 two circular ramparts from a Celtic fortification were recognized. The ramparts ran concentrically around the two mountain tops with the inner rampart measuring 2.1 km and the outer rampart measuring 3.1 km (see map).

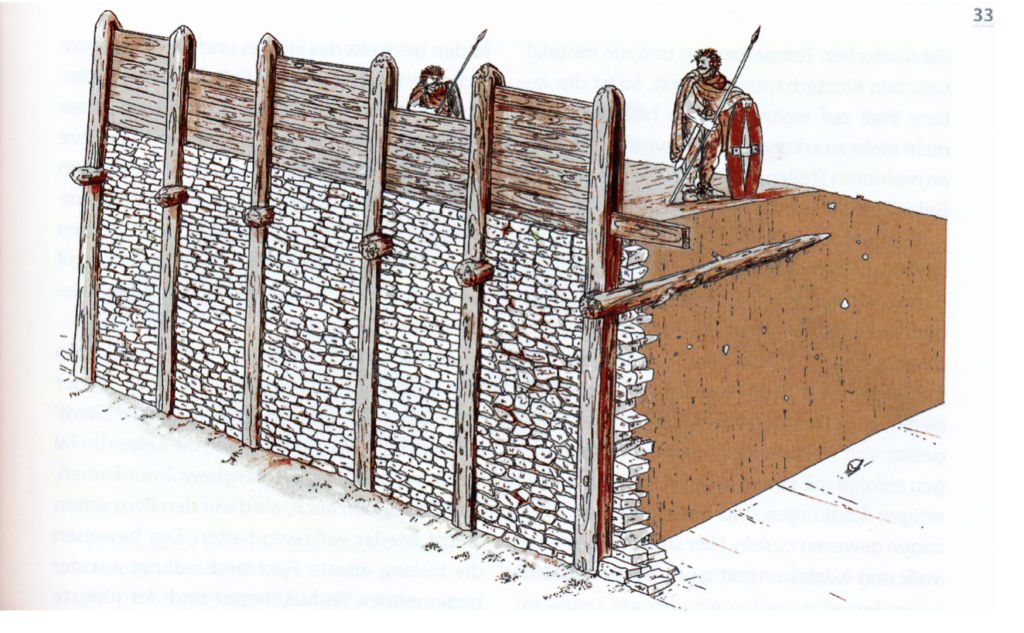

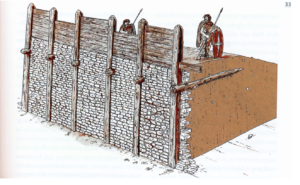

Later, around 400 residential platforms, which were hut spaces terraced into the slope, were found in this area. This makes the fortified settlement one of the largest Celtic structures in Baden-Württemberg. The ramparts are the collapsed remnants of a huge wood, stone and earth construction, a typical Celtic „post-slot wall“. This was confirmed by a teaching excavation in the summer of 2019.

Keltische Pfostenschlitzmauer © KMH (B. Pfeifroth/P. Marzolff).

This reconstructed post-slot wall You can visit near the Waldschänke: (Foto SGH)

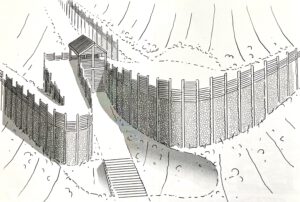

In the north-east section of the outer rampart was a goal that might look like this:

Nordwest-Tor des Inneren Ringwalls, rekonstruiert von Markus Ball in: Handschuhsheimer Jahrbuch 2022

The finds on the mountain show a fortified Celtic settlement on and around the northern tip, probably in direct succession to the Urnfield settlement there.

Arm- und Fußringe aus Bronze und wirbelförmige Perle (Frühlatène) © KMH (E. Kemmet)

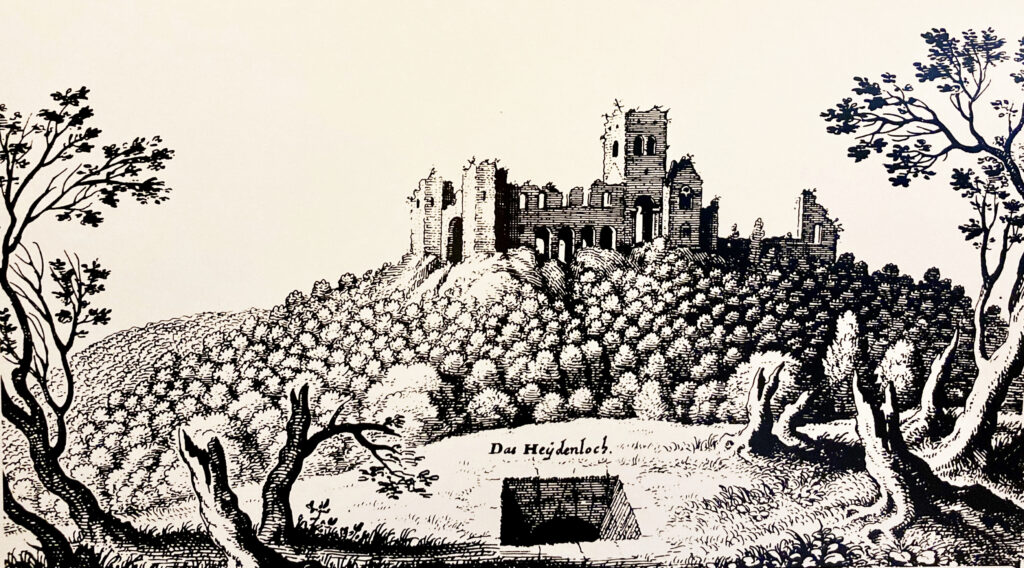

A summit shrine could have been located on the artificially extended hilltop – a long tradition of veneration at this point indicates this. Providing archaeological evidence of a prince’s seat and the corresponding housing development to the south was made impossible by the construction of the „Thingstätte“ during the Nazi era. On the southern hilltop, on the edge of the settlement, there is a 56 m deep shaft in the red sandstone, the so-called „Heidenloch„. Roman and medieval traces of expansion indicate the – unsuccessful – attempt to build a well or a water cistern here. The location of the place on the summit and the geology made it impossible for such a construction. Instead there are many indications for the existence of a Celtic sacrificial pit, as has been found elsewhere, even if not of the imposing depth of the Heidenloch.

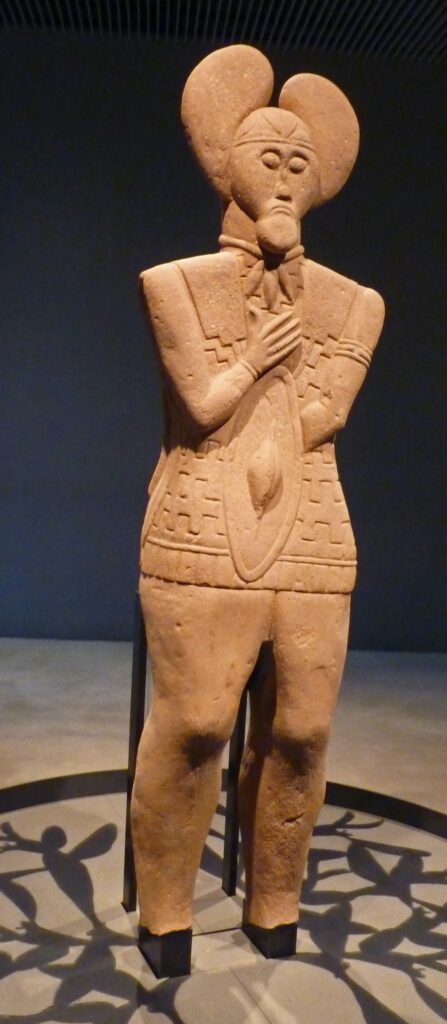

At the end of the 19th century a life-sized head of a sandstone statue was discovered in the Bergheim district, not far from the Neckar. It shows, as we know today, a Celtic “prince” with the typical leaf crown and it probably comes from his (still) unknown burial mound.

Keltenkopf.Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe. Foto: Thomas Goldschmidt

Similar finds on the Glauberg in Hesse indicate cultural and economic connections between the two princely seats around 370 BC.

Fürst vom Glauberg

After all, the Celtic fortress on the Heiligenberg controlled the trade routes in the valley and on the Neckar with a connection to the Danube, and thus its inhabitants lived from trade and handicrafts. The discovery of two iron bars indicates this.

Keltische Eisenbarrenm Reste eines Gusstiegels, Eisenschlacken © KMH (R. Ajtai/VE.DO)

Eisendepotfund aus der Mittellatènezeit © KMH (R. Ajtai/VE.DO)

At the time of the “Celtic migration” (from 400 BC) the importance of the fortification as a power center on the lower Neckar waned, the population thinned out. Nevertheless, people settled within the ramparts, as evidence shows. It is possible that even around 200 BC there was a late Celtic city on the mountain, an “oppidum”, which has (yet) to be proven by finds.

But no later than 100 BC the Celtic traces are lost, the remaining Celtic population merges with the Germanic immigrants, the Neckarsueben. What remains are the ramparts and the memory of the Celtic sanctuary on the northern crest. The remains of a Roman temple in the main nave of St. Michael’s Basilica, consecrated to Mercury (a syncretism of the Celtic god Visucius and the Germanic god Cimbranius) bear witness to this.

Romans

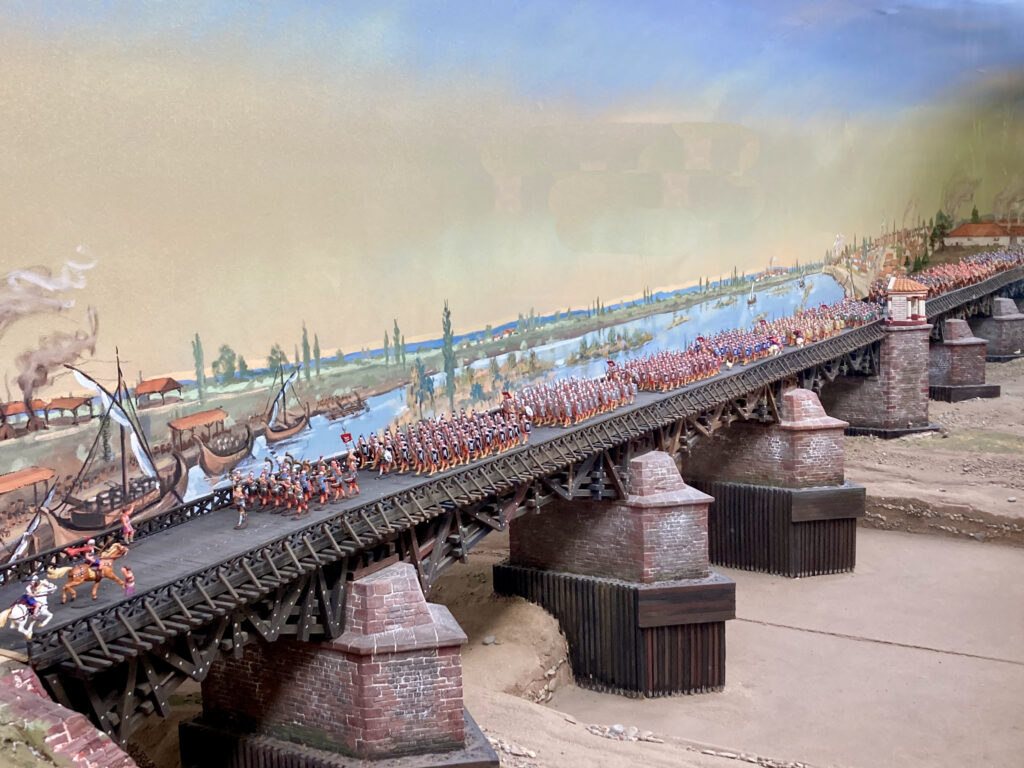

In the time of Emperor Vespasian (69-79 AD), a number of forts were built on the right bank of the Rhine in the so-called “Agri Decumates” or “Decumation Fields” in Germania Superior to protect not only this area but also the area towards the east along the Limes . The main town in our area was LOPODVNVM (Ladenburg), where a second castrum was laid out around this time and soon after the construction of a city and the construction of a large forum began. In Neuenheim a castrum was laid out and a Neckar bridge built, later a second fort followed, and around the year 200 a Neckar bridge on stone pillars was built.

Römerbrücke Neuenheim.KMH

The reason was the construction of a military road east of the Rhine from MOGONTIACVM (Mainz) via LOPODUNUM to AQVAE (Baden-Baden) and ARGENTORATE (Strasbourg), with another junction also to AVGVSTA VENDILICORVM (Augsburg). In addition to the military camp in Neuenheim, small civilian settlements emerged, in which handicraft businesses with brick and ceramic production were predominant. An extensive burial ground has been proven.

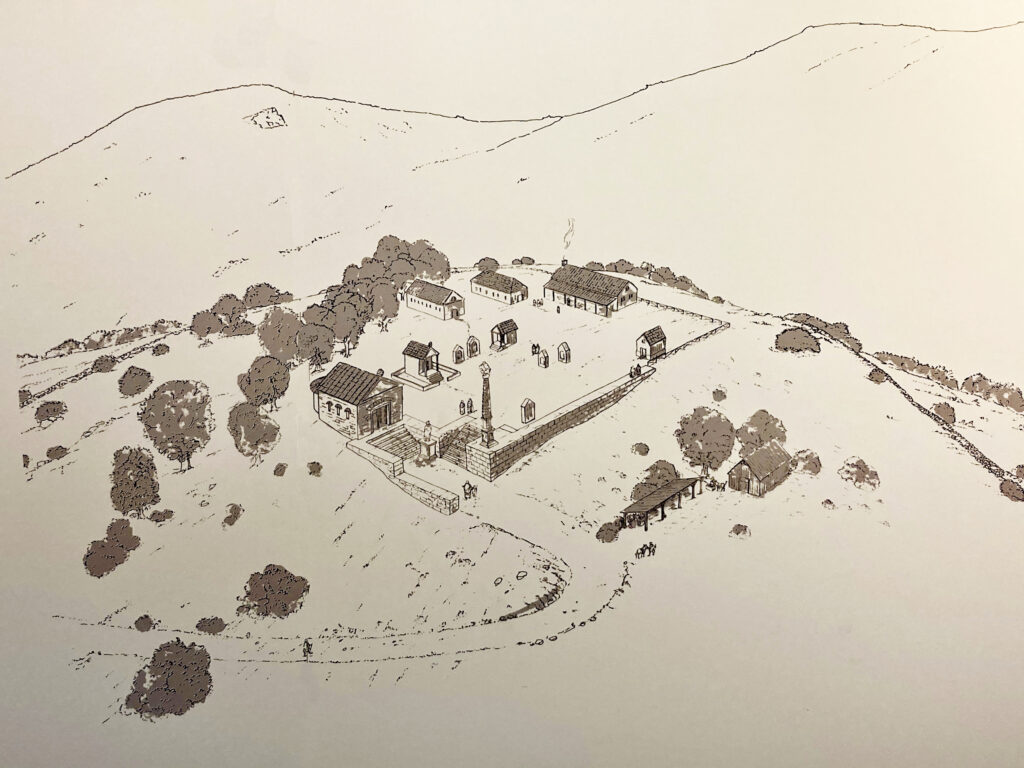

A holy district was laid out on the Heiligenberg in the 2nd half of the 1st century.

Römischer heiliger Bezirk (Rekonstruktion)

The center and most important building was a Temple of Mercury. In the central nave of St. Michael’s Basilica dark stones indicate its outlines. A north-facing rectangular hall with an apse was painted brightly on the outside with a red line of grouting, on the inside it was clad with painted plaster, red porphyry and white marble.

Merkurtempel (Rekonstruktion) © KMH (B. Pfeifroth:P. Marzolff)

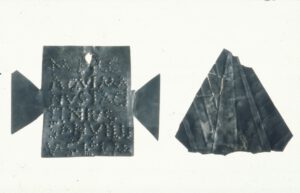

Through dedicatory inscriptions in stone and votive tablets, we know that a MERCVRIVS CIMBRIANUS or MERCVRIVS VISVCIVS was venerated here, i.e. that here, in the sense of the Interpretatio Romana, the Roman god was seen to be equal with a Germanic or Celtic god.

Weiheinschrift für Merkur Cimbrianus © KMH (E. Kemmet)

Rekonstruktion eines silbernes Votivblechs aus dem Merkurtempel © KMH (R. Dale)

Silberne Votivbleche für Merkur © KMH (R. Ajtai/VE.DO)

Remains of two giant columns of Jupiter were also found as well as references to other sanctuaries and smaller buildings.

Jupitergigantensäule © KMH (E. Kemmet)

From the year 260, the Roman presence ended with the Alamanni invasions, when the area on the right bank of the Rhine had to be largely abandoned.

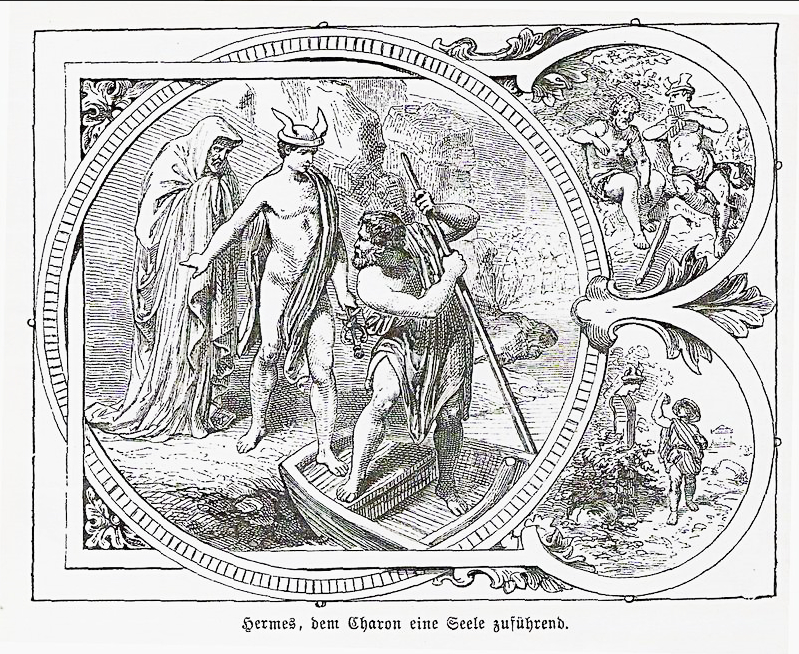

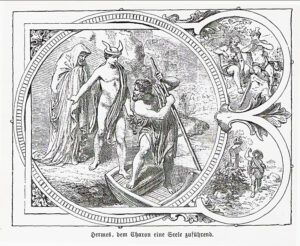

Francs

From the time of the Migration Period there are few finds that prove that the holy mountain was still being climbed. It is likely that the sanctuary was plundered after Roman times. After the Christianization of the Alemanni in the 5th century, who were predominant in our area, the still preserved Temple of Mercury on the Heiligenberg was rededicated into a Christian church, which was probably consecrated to the Archangel Michael from the beginning. Even if the god of traders and pickpockets and the biblical dragon slayer seem to have little in common, there are also surprising similarities. Like Michael, the god Hermes / Mercury is a feathered messenger of the gods, and the Greeks also call him the “Psychpombós”, the companion of the deceased souls via the Styx into Hades. And Michael is also considered a soul companion after death. If we take note of the fact that graves from all times for 3000 years – except the Roman period, but particularly intensively in the Merovingian-Franconian phase – have been found on the Heiligenberg, then this commonality of the two mountain patron saints fits well with the place.

During the Franconian era, a royal castle was built on the Heiligenberg – probably in connection with the Franconian royal court in Ladenburg – some buildings from this period have been archaeologically proven, including a mighty tower with massive masonry – a kind of keep, as found on later castles, or a residential tower – in the area of the later enclosure. Remnants of the old Celtic walls were probably also used to secure the complex, because mortar-walled chamber gates were discovered in two places, as they are known elsewhere from the Carolingian period. Fortification walls from the time of the royal castle can still be seen on the westernmost edge of Paradise.

Fränkische Burg (Rekonstruktion) © KMH (B. Pfeifroth/P. Marzolff)

On this fortress, now called Aberinesberg or -burg, a branch of the Frankish imperial monastery Lorsch was set up in the 2nd half of the 9th century. Lorsch had many possessions around the Heiligenberg, and so it was only logical that it were located there with a few monks in order to better manage its goods and income. (Almost all the villages around Heidelberg, today mostly suburbs, have their first documentary mention in the 8th century, collected and recorded in the Lorsch Codex in the 12th century.) And the Lorsch abbot Thiotroch had a new St. Michael’s Church built on the mountain around 870 (now the patronage is documented), which had parts of the Roman walls included in the construction.

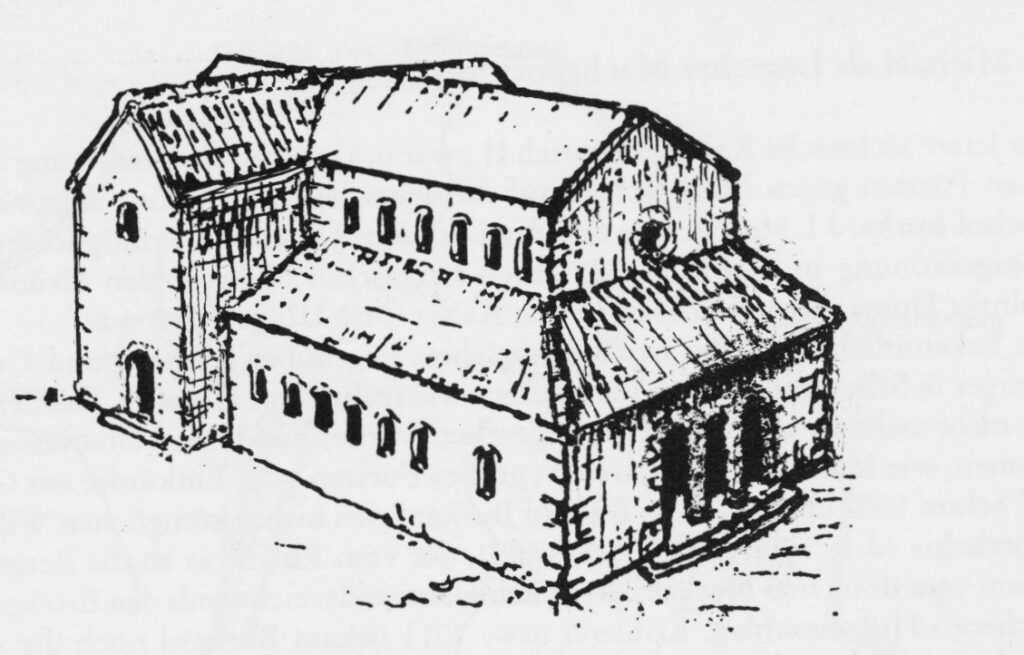

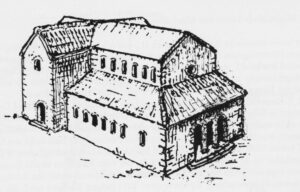

St Michael im 10. Jh. v.Moers-Messmer 1987

This resulted in a coexistence of royal and monastic presence on the mountain. Then in 882 King Ludwig III. donated the Aberinesburg to Lorsch Abbey.

Benedictine / Premonstratensian

We can also assume that there were no monastery buildings in the sense of a cloistered monastery, but that the monks probably lived in the buildings of the castle. Since the branch of Lorsch on the Heiligenberg also received the associated property with the donation, there was a lot of money, and so St Michael’s Church was rebuilt many times during the 9th and 10th century, at the end (around the year 1000) stood a three-aisled basilica with a transept and three choir apses. A west crypt was installed as a base to statically secure the mighty westwork and its two towers on westward sloping ground.

In 1023, Emperor Heinrich II granted the Lorsch abbot Reginbald, the later builder and bishop of the Speyer Cathedral, permission to build a regular monastery on the Heiligenberg. Apart from the choir and the east crypt, the previous church was removed and rebuilt with larger dimensions as a three-aisled basilica. According to the Lorsch Chronicle, it was splendidly furnished, and the luxury of the two (!) generous stair towers still demonstrates today that there were obviously considerable funds available here. In order to statically secure the mighty westwork with its two towers on the westward sloping ground, a west crypt was installed as a base.

Archivolte eines mittelalterlichen Schmuckportals aus dem Kloster © KMH (E. Kemmet)

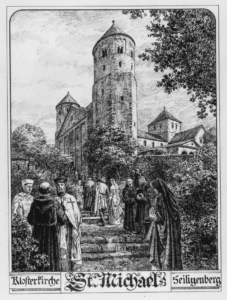

In the west, a paradise or atrium called forecourt was built, but it was rebuilt many times over the next few centuries and mainly used as the cemetery of the monastery. The enclosure, the living and working area of the monks, was not built beside the church as in most of the monasteries but, because of the structure of the terrain, in the east of the church. The monks were Benedictines, the Monastery of St. Michael remained a branch monastery of Lorsch, so it was not led by an abbot, but by a provost. Merian’s depiction from the 16th century shows a crossing tower, which was perhaps added later and was not a bell tower. It probably stood next to the northern chorus apse, and also only dates back to the 15th century.

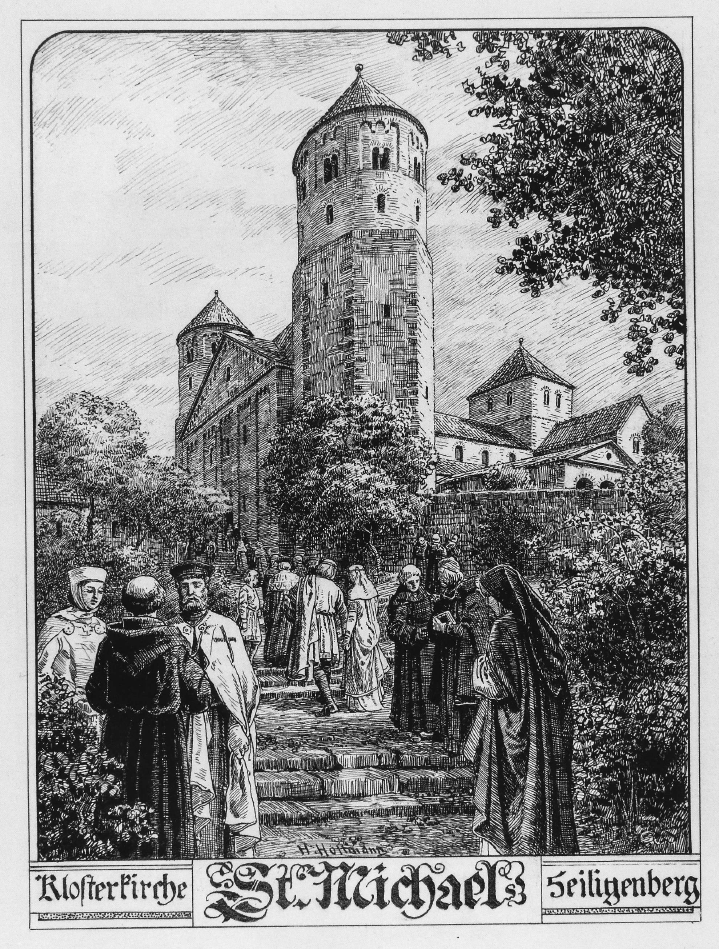

St. Michael von Südwest. Hoffmann

In 1069 the former abbot Friedrich von Hirsau was accepted into the monastery. According to tradition, he was a particularly pious cleric who was recalled from his office by the lord of the monastery, the Count of Calw, due to an intrigue in the local monastery. In order to spare him the shame of having to continue to live in Hirsau under these circumstances, the Lorsch abbot Uldarich arranged a kind of retirement home for him in St. Michael’s monastery. However, he died in 1070, and was loved in the surrounding villages because of his charity. Legends of light and angelic appearances surround his death, and to this day Friedrich von Hirsau is a venerated saint in the Diocese of Speyer, although never canonized by the church as such. With great certainty he found his final resting place in the grave dug into the rock in the middle of the east crypt, which became a place of pilgrimage, especially on May 8th. Even today you can often find a bouquet of flowers on the grave plate, which was renewed because the grave was destroyed in the 19th century.

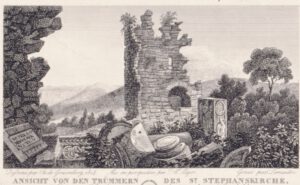

Around 1090 Arnold, a Benedictine monk, built a hermitage and an oratory (small chapel) on the front summit. About 4 years later, with the support of the Lorsch abbot Anshelm, another smaller branch monastery was founded at this point, the remains of which can now be seen as ruins. It was consecrated to St. Stephen and later also to St. Laurentius.

Stephanskloster (Rekonstruktion nach v. Moers-Messmer)

A knight from Handschuhsheim named Rifrid did not only attest witness to the monastery deed of foundation, he probably also bequeathed part of his fortune to the monastery. In 1932 a tombstone was found with a Latin inscription saying that Rifrid’s wife or widow wishes to be buried here (in the monastery) and that she shall bequeath her property to the monastery on the condition that the monks preserve her memory. The date of death is given as December 23rd without a year. A copy of the gravestone, the original of which is in the Kurpfälzisches Museum, can be seen today in the western part of St. Stephen’s Church. (This tombstone is the oldest post-antique written testimony that was found on Heidelberg soil.) Statements in the Lorsch Chronicle insinuate that Rifrid moved to the Holy Land with the first crusade in 1096 and probably did not return.

Grabplatte der Hazecha aus St. Stephan © KMH (P. Pfeifroth / T. Schöneweis)

Abbot Anshelm was also buried in St. Stephan in 1101. On the day of his death, June 25, a procession moved from Handschuhsheim to the monastery. The name has been retained from the processional path, distorted into „Amselgasse“. His grave could not be found.

In the 13th century, Lorsch lost its dominant position, at the instigation of the Archbishop of Mainz its immunity was lifted, the Benedictines had to leave Lorsch and were replaced in 1245 by Premonstratensian Canons from the Black Forest monastery of All Saints, who some time later also took over the St. Michael branch. The Heiligenberg, which thenceforth received its current name („Allerheiligenberg“), belonged from then on to the office of Schauenburg, which was under the supervision of Mainz.

That only changed in 1460 with the victory of Elector Frederick the Victorious near Pfeddersheim in the Mainz Diocesan Feud (Stiftsfehde), which brought the office of Schauenburg and thus Heiligenberg into the control of the Electoral Palatinate.

Under the Premonstratensians there were some renovations in the church and monastery. Early Gothic windows were inserted into the apses, part of the cloister was later equipped with Gothic tracery windows. Apart from the calefactorium, other rooms were then also equipped with heating facilities, and tiles from a luxurious stove were discovered. During the time of the Premonstratensians, the monastery increasingly became a center of pilgrimage.

In addition to the two aforementioned processions on the Heiligenberg, two others have passed down to us over time . A hall procession called „Rolloss“, which reminds of a path name in Handschuhsheim, would take place on the Monday of the 6th week before Easter and it probably dated back to old pagan fertility rites. It can be assumed that things were quite rough on these occasions, so much so that in 1423 the Heidelberg University forbade those who belonged to the institution to participate and would punish by fine if they so did. Since the Premonstratensian period there has been a procession on the eve of All Saints‘ Day, that is on October 31st, in which the elector also used to take part and with which there was a fair on the site north of the monastery.

In the 15th century, the monasteries on the Heiligenberg seem to begin to decline, and the number of monks also decreased. According to a report to the Elector in 1503 the bell tower collapsed one night and killed three monks in their dormitory. The tower had previously been damaged by an earthquake in 1474. In 1537 we learned from Micyllus, who was a humanist from Heidelberg, that he had already found a ruin on the rear mountain peak. Until the middle of the 16th century, the St. Stephen’s Monastery seems to have been inhabited by a few or, at the very least, one monk („Brother Moritz“).

Heidenloch und Michaelskloster. Merian 1645

The Age of the Ruins

“You green mountain, you with two peaks

Like Parnasso, you high rock, with you

I wish to stay in peace for and for … „

This is how the baroque poet Martin Opitz, who was a student in Heidelberg around 1620, describes the Heiligenberg in a sonnet and compares it to Mount Parnassus, the Mountain of the Muses.

Meanwhile, the mountain has become more fascinating because of its nature and extraordinary shape, and its long history of settlement and worship of higher powers is becoming increasingly forgotten. In an engraving by Matthias Merian from 1645, the Monastery of St. Michael can still be seen as an impressive ruin despite the fact that it was given to the University of Heidelberg as a quarry. It seemed to have defied total decay for over a hundred years since its first mention as a ruin (1537).

However, archaeological looting and excessive stone robbery caused by the reconstruction of the war-torn villages at the foot of the mountain after the Palatine-French War of Succession (from 1689), soon only left the foundations of the two monasteries which too gradually became overgrown.

Die Türme des Klosters als Steinbruch (nach einer Zeichnung von Ph. Förster 1830)

What remains is a mysterious memory of „pagan“ and medieval antiquities that moved the romantic Victor Hugo to visit the mountain at night on his trip to Germany in 1840.

Ruine des Michaelsklosters 1814 (Stahlstich von de Graimberg) © KMH

People only began to be interested in the history of the mountain from 1860, when Julius Näher discovered the ramparts and – initially – declared them to be „Germanic“. The newly awakened interest in the prehistory of Heiligenberg certainly has something to do with the unification and nation-building of Germany. This explains why from 1886 (Wilhelm Schleuning) until the 1930s (Carl Koch) excavations took place at the monasteries and the ramparts.

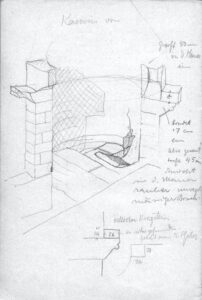

Carl Koch, Skizze des Kamins im Kalefaktorium

The city of Heidelberg, owner of the Heiligenberg since 1903 through the incorporation of the village of Handschuhsheim, showed great interest in the research at the time. Between 1910 and 1920 the painter Heinrich Hoffmann frequently went to the mountain and created meticulous drawings of the ruins. As a result he reconstructed the – possible – historical condition with a pencil, which has today become a valuable source of images.

The construction of the observation tower and its stones (1885) in the middle of the ruins of the St. Stephan monastery can only be regretted today. However, even worse is the construction of the “Thingstätte” which was placed in the middle of the Celtic settlement area by the “Reichsarbeitsdienst” (Reich Labour Service) in 1934/35. This destroyed several historical layers that cannot be restored. The replica of an ancient theater, designed for 15,000 visitors and intended by the Germanophile Thing Movement for German-national propaganda purposes, no longer fitted into the agenda of the National Socialists in 1937. Initially it was renamed into „Feierstätte“ (which roughly translates to Celebration Centre) – but thereafter it simply became useless!

Thingstätte 1935 (Stadtarchiv Heidelberg)

It is only from 1950 onwards that the archaeologist, Berndmark Heukemes, reminds us of the historical importance of the mountain. It was he who founded the „Schutzgemeinschaft Heiligenberg“ in 1973 in order to preserve the monuments. He also initiated a chain of explorations and repairs: A refuge was built above the Heidenloch, the ruins of both the St. Stephan (Bert Burger 1996) and St. Michael (Peter Marzolff from 1980) monasteries are being restored and partially reconstructed, so are the two west towers and the west crypt.

The reason for thorough repairs and archaeological research in St. Michael was the continuing decline of the ruins of the two western towers. As a Heidelberg archaeologist and above all as chairman of the Heiligenberg Protection Association, Berndmark Heukemes decided to sound the alarm. He succeeded in getting the city of Heidelberg, the University and the State of Baden-Württemberg on board and providing two million DM so that between 1978 and 1984 the entire ruins of St. Michaels Monastery could be restored and also partially archaeologically examined. Under the direction of the architect Bert Burger, the stumps of the two west towers were renovated and made accessible. The west crypt – up until then a hole filled with rubble – had vaults recreated which were reminiscent of those from around 1200. In the cloister wing wall sections were added in the historically correct sense and incorrect reconstructions made by the Labor Service in the 1930s were eliminated.

The excavations carried out by Peter Marzolff – Institute for Prehistory and Protohistory from the University of Heidelberg – in selected parts of the complex yielded surprising new findings: the foundation walls of a Roman temple of Mercury with the apse facing north were exposed under the floor of the central nave. The previously suspected existence of a Roman peak sanctuary was thus archaeologically confirmed. Today the layout of the temple is marked by cobblestones in the monastery church. The efforts of the Schutzgemeinschaft to seriously take care of the preservation of the ruins were thus crowned with success. Since the secured ruins still have to be regularly maintained and repaired, the Schutzgemeinschaft subsidizes the work that has to be done in line with its purpose.

Ausgrabung in der Kirche. Foto: Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte Universität Heidelberg

In a similar fashion, a small scale educational excavation was financed together with the Kurpfälzisches Museum Heidelberg, the Working Group for Archeology in Baden and the State Monuments Office. (Schöneweiß 2019). This excavation has proven the construction of the inner circular wall as a Celtic post-slot wall and this has led to an interest in doing a more extensive excavation. There are many questions about the Celtic history of the mountain that are still unanswered.

By the way, since 1996 the “Celtic Path”, with its display boards, has connected the historical sites. Hikers and visitors can find a relaxing break on the saddle between the two mountain tops – near the large parking lot – in the „Waldschenke“ restaurant, which has been in existence since 1929.

The Heiligenberg as a “Holy Place”

One of the special features of the Heiligenberg is that we can assume that it was continuously used as a mountain sanctuary dating, at least, as far back as the Celtic settlement all the way up to the end of the monastery era – albeit with short interruptions. On this basis, the question to be examined is whether there was a special religious theme that connected the sanctuaries of the various cultural epochs with one another, i.e. a continuum in terms of content. It is certain that a sanctuary, in some form or another, also belonged to a prince’s seat

The archaeologically oldest evidence of a sanctuary on the Heiligenberg is given by the remains of the Celtic settlement between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC. After the Celtic head found in Bergheim could be interpreted as part of a grave figure of a Celtic „prince“ analogous to the monumental figure on the Glauberg, it could be concluded that there was a „princely seat“ on the rear summit of the Heiligenberg in the 5th century. It is certain that a sanctuary, in some form or another, belonged to a prince’s seat. After all, there are 2 things that archaeologically prove this on the Heiligenberg:

- When the area of the Roman Temple of Mercury was uncovered during the excavations in the 1980s, the archaeologists came across an approx. 80 cm deep prehistoric pit with bones and other remains, which were in the center of the temple – i.e. under the statue of the god Mercury – (and the later basilica). This could be an indication of the assumed Celtic sanctuary on the summit that was apparently carefully taken over by the Romans and turned into their sanctuary. It suggests that it was still used by the population around the Heiligenberg, even after the Celtic settlement on the mountain was abandoned,.

- Even though the origin of the Heidenloch is uncertain, (who created it, when and why) there are good reasons to assume that it was the Celts, especially since they were the only ones who had the „manpower“ for such a large project and also because this pit was located on the outermost south-west edge of the area of the inner curtain wall (circular rampart).

For geological reasons (water veins in the mountain as well as the nature of the sandstone), it is unlikely that it was used as a well or a cistern system. Any such attempts, for example by the Romans to use the Heidenloch in this manner, remained futile. This leads us to believe that the Heidenloch was used as a sacrificial pit.

If this was the case, it would make sense to put the pit on the edge of the settlement because of the possible smell of the decaying sacrificed animals. Sacrificial pits have been found in various Celtic holy districts („Nemeton“) in southwest Germany, but no deeper than 35 m. In the religious imagination of the Celts, they represented a place that symbolized the transition from life to another (under) world and were apparently dedicated to a Celtic earth deity, according to Dirk Krauße, State Archaeologist of Baden-Württemberg in a ZDF film about Celtic finds near the Heuneburg.

In Roman times, it was primarily Mercury (along with other Roman gods) who was worshiped here and whose temple was the center of the sacred area of the Romans. Mercury was particularly popular among the Celts, as mentioned by Caesar in Book 6 of his De Bello Gallico. He was often identified with the Celtic god Teutates, but there is a votive tablet on the Heiligenberg, which equates Mercurius with the relatively unknown Celtic god Visucius on the left bank of the Rhine. There is also mention of Mercury as „Mercurius Cimbrianus“, that is, as a Germanic god, who was mainly equated here with Odin (or Wotan). As we know, this was made possible by the “interpretatio romana”, which promoted the equation of the Roman Olympian gods with the respective provincial gods as a part of an integrative religious policy.

After the end of the Roman and Alemannic presence, the pagan temple was Christianized in Merovingian / Frankish times and, as we can assume, consecrated to the Archangel Michael (the patronage of Michael is only guaranteed from 890). And henceforth, the Archangel Michael tends to succeed the Roman god Mercury in comparable places.

And they actually have a lot in common. We mostly know Mercury as the god of traders and thieves. But he is also a winged messenger of the gods, and the Greeks called their Hermes „Psychpombós“, i.e. as a soul companion who supports the deceased as they cross the river Styx into Hades.

Hermes als Seelengeleiter

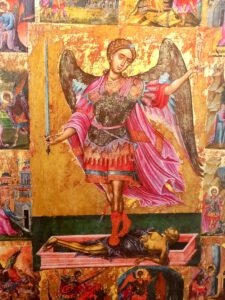

Michael, also a winged messenger of God, the Archangelus, has the quality of a soul companion, and he is the weigher of souls at the Last Judgment.

St.Michael als Seelengeleiter (Griechisch-orthodoxe Ikone aus Kreta)

It should also be mentioned that in St. Michael’s Basilica of the 10th century there was a reliquary shrine or grave in the middle of the central nave, i.e. precisely at the point where the pre-Roman sacrificial pit and the image of Mercury had been. And in the 5th/6th century a central grave was installed along the border of this pit. It was around this grave that other graves were organised. Those buried here were probably venerated by the Lorsch monks as early witnesses of faith.

In addition, the Heiligenberg was a popular burial site at various times from the Urnfield period to the end of the monastery period. It was not a cemetery, but those who could afford it, for various reasons, were happy to be laid to rest “up” here in this holy place between heaven and earth, a place with a magnificent view. This probably does not apply to the Celtic and Roman times, but even more so for the Merovingian / Frankish times, and also for the monks of the later monastery found their final resting place here. And there were always lay people, men, women and children who were buried here during the monastery period.

And so for at least 2 millennia, from the Celtic settlement to the end of the monastery period, there is a continuous theme of sanctuary on the Heiligenberg: It was a good place for the transition from this life to whatever imagined hereafter, accompanied by a deity or an archangel. This was the space between heaven and earth, a sacred place where one thought beyond the little worries of everyday life and confronted the difficult topic of a post-mortem existence. The fact that people were buried up here in the Urnfields period provides room for speculation that there was perhaps an even older tradition of dealing with the afterlife on the mountain.

In fact, the story of the local saint of the mountain fits in well with its history. One could exaggerate by saying that Friedrich von Hirsau came to the Heiligenberg to die. His sought after asylum from the Hirsau monastery – where he was “bullied” and falsely accused of adultery and where he lost his position as abbot – did not last long. He did not live here for a very long time, and the wonderful circumstances of his death that have been told make him the venerated saint of the region and his grave the destination of pilgrimages to the monastery and the east crypt. And this contains more than a relic, it contains Friederich’s grave that is set into the rock. A grave as a pilgrimage destination, how fitting to the history of the mountain!